I know it’s after the two deadlines we agreed on, and my apologies, but if possible (after much wavering), I’d like to put my mapping project up for discussion.

Overview

Death is an inescapable and universal part of being human, but the rituals and care provided by the living to their dead are shaped by many changing factors, including emotional, physical, financial, societal, and spiritual/religious. Cemeteries are one type of designated space created by the living for the care of the dead. Archeologist Elizabeth Meade says, “Because of this responsibility, burial grounds can serve as significant cultural spaces utilized by and integral to the cultural traditions of the living. For the living, cemeteries encapsulate both the physical aspects of death and utilitarian nature of decay as well as the cultural influences that govern death ritual and the social transition from life to death” (Meade 2020). There’s also an inherent tension between remembering and forgetting that happens in cemeteries, with human memory and grave markers both subject to erosion. Within a city like New York, especially on the island of Manhattan, a large population confined by a definite geographical area adds to this tension. A population of this size necessarily requires the care of a larger number of dead, and it also means that the physical space allotted for the dead competes with the space allotted for the varied activities of the living.

This project aims to create a story map to visualize cemetery obliteration in Manhattan between 1820 and 2020. In addition to the nice numerical symmetry provided by these two years as end points, the population of New York City (then still just Manhattan) more than doubled between the 1800 and 1820 Census, and 1820 also narrowly precedes the burial restrictions implemented in 1823. 2020 will also still be a very recent past when this project is being built, and it is a year very much influenced (if not defined) by the global coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. As much of the legislature regarding cemeteries in New York in the 19th century was written and passed in response to outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera, it will be illuminating to investigate their effects at a time when the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is still being examined and understood in the present.

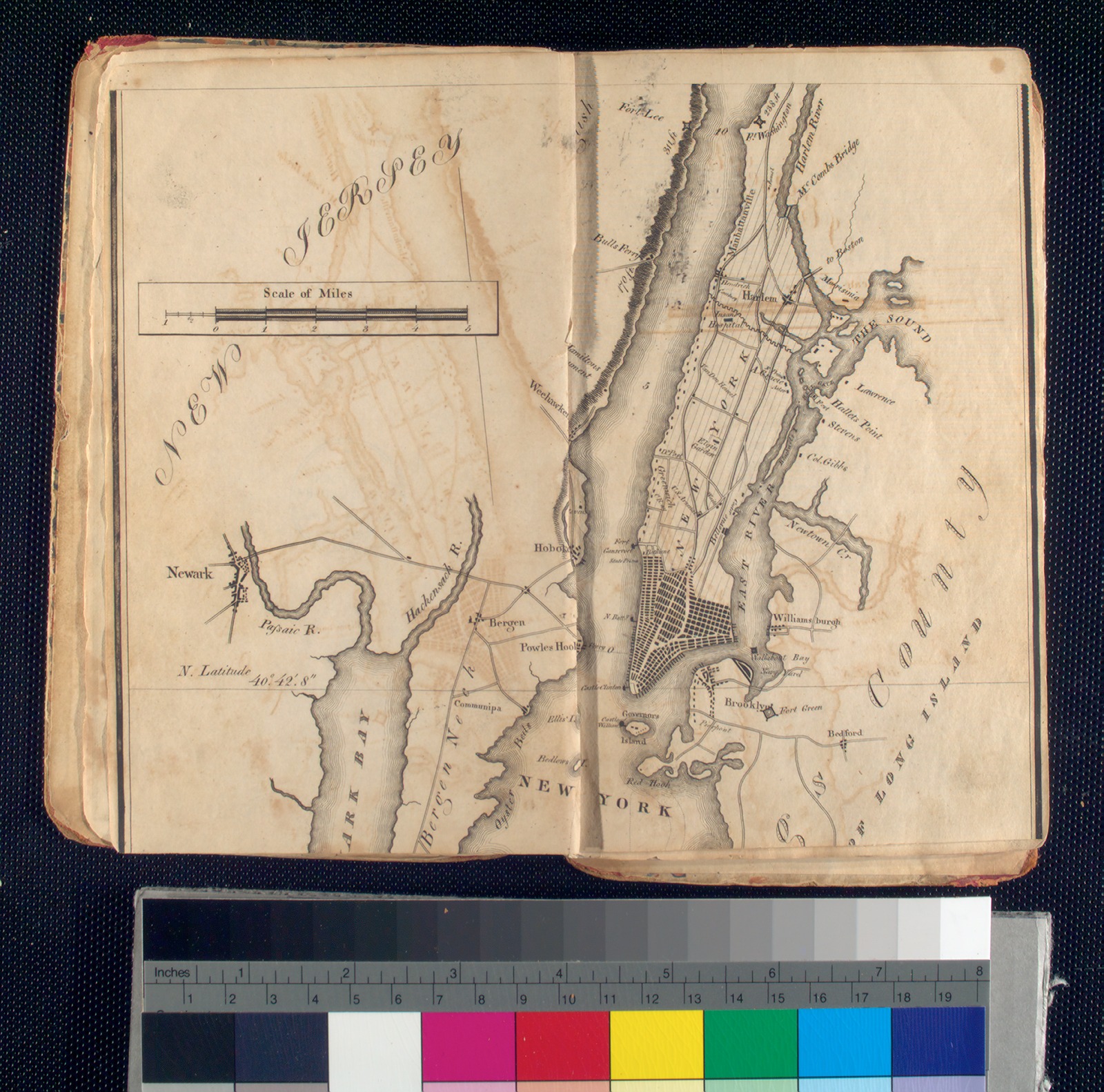

The base layer of the map will show the existing cemeteries in Manhattan as of 1820, overlaid on a historical map of Manhattan available from the NYPL using their free Map Warper tool (perhaps this one), including their specific sizes and locations. Informational pop-ups will also include the year each cemetery first came into use, the type of cemetery it is or was (such as commercial, religious, public, or familial), and overall demographic information about the people who were buried there. For the cemeteries that no longer exist as such, the map will indicate what project originally replaced it, either partially or completely (e.g., infrastructure such as roads and subway lines, parks, or buildings). There will also be images of what the area looked like in 2020, as well as median household income and demographic information for the Census tract in that year.

Intended Audiences

The intended audiences for this project are scholars and the general public interested in the following:

- cemetery studies

- urban planning

- local history

- historical maps and mapping generally

Contribution to Digital Humanities

This map will help humanities scholars, cemetery studies scholars, local historians, and all interested New Yorkers explore questions related to urban planning and sustainability and also questions about belonging, community building, and how power structures determine who “deserves” to be remembered and the impact these have on living populations. Complementing the above data, the story portion of the project seeks to explore the considerations that went into repurposing the land from cemeteries to other uses. How were these proposals first brought forward, and by who? City design is a type of infrastructure, and the decisions on how to build it and how to alter it are necessarily political (Star 1999). As much as infrastructures are built to be of service to people, they also impose limitations on how we interact with and experience them (Gil 2016). How people live and die in the city affects and—perhaps more so—is affected by its landscape.

This project also seeks to find trends regarding the cemeteries that were preserved and the ones that were obliterated. For instance, several prominent parks in the city—Washington Square, Madison Square, and Bryant Park—were sites for potter’s fields where the unidentified, poor, and those of all classes who died of yellow fever were buried (French 2020). How does this trend reflect both historical and current power structures, and what are the implications for the surrounding neighborhoods? Even if a public park could be argued to enrich the public at large, its creation likely also substantially increased the private wealth of those who bought and developed the land around it. So what ultimately is the public good—how is it defined and by whom? This map will help users explore these land use transitions and the relationships between private and public spaces further. In addition, there are repurposed cemeteries where the bodies have not been moved and the sites remain unmarked. What does this collective forgetting—in some cases purposeful—of a cemetery mean for living descendants, and how do cemeteries contribute to our understanding and claims of belonging to certain communities and specific locations?

Environmental Scan

There is much interest in cemetery studies as it relates to personal genealogies and family histories. This mapping project will view cemeteries on a larger scale and view them in relation to and as part of the urban landscape in New York City.

The New York City Cemetery Project, created by anthropologist and museums and archives specialist Mary French, comprises archival research and a narrative snapshot for each cemetery, accompanied by historical images, newspaper clips, and snippets of maps, for approximately 350 cemeteries in the city dating from the colonial period onward. It is a tremendous project offering a wealth of knowledge on the cemeteries she has researched; however, the blog-like presentation of the information doesn’t easily allow for examination of the cemeteries in comparison with one another or an understanding of the physical spaces they occupy or occupied.

In her anthropology PhD dissertation for The Graduate Center, City University of New York, Elizabeth Meade sets about providing the most complete record of historical cemeteries in the five boroughs. She admits that her study is incomplete as it includes only cemeteries that were intentionally built and recognized as such. It is also based on the historical records available from the colonial period onward, and so excludes the burial activities of the indigenous people pre-contact. Furthermore, as record-keeping and preservation are timely and not without significant costs, much of the available records likely skew toward cemeteries and groups of European descent with means.

Acknowledging these limitations with the utmost sensitivity, this project will build most of the data pertaining to cemeteries in 1820 from Meade’s dissertation. Her dissertation presents the maps in segments (as a limitation of the size of the page), but she also has built a website with the full map. The story map proposed herein will work to combine narrative and map into one cohesive experience. It will also aim to compare the historical demographic data with more current demographic data to help better understand how communities have changed. The story map proposed here will focus on the absence of certain cemeteries in 2020 because those absences are full of meaning that needs to be identified.

This project is the first phase of a further exploration of the ties between cemeteries and other outdoor spaces in the city.

Final Product and Dissemination

The final product will be a interactive and multilayered map that compares the status of these historical cemeteries between 1820 and 2020, along with historical and more recent images, and comprehensive text providing background on legislature and trends affecting the landscape of the city.

Project participants will share links to the final project via their various social media streams, namely, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. They will reach out to those in charge of the social media accounts within The Graduate Center community to share our posts, including professors within the MA in Digital Humanities and MS in Data Visualization programs, the CUNY GC Digital Initiatives team, and GC Digital Fellows team.

Pertaining to New York City history, they will also reach out to local media outlets such as Gothamist, New York Daily News, and WNYC to provide coverage of our project, or at least share the social media posts to a wider audience. Given their special interest in creating maps and previous coverage on cemeteries, the project lead will write up a post summarizing the mapping project to share with Atlas Obscura for them to share on their site and via their social media channels. The project lead will also share write-ups with the websites Untapped New York and 6sqft as they have also previously posted content about New York City cemeteries.

Skillsets Needed

Much of this data already exists as part of Elizabeth Meade’s recent PhD dissertation in Anthropology at The Graduate Center. I will reach out to her about sharing her data.

I would also like to consult with and interview an urban planner (I know someone, though he is based on Long Island) and local historians familiar with the time period.

I believe a large portion of time will be spend collecting demographic and financial information for the relevant Census tracts, and then cleaning that data along with Meade’s data from her dissertation.

There will also be a significant amount of time spent writing and editing the accompanying text.

My experience with mapping tools and data analysis is very limited, so this project will greatly benefit from someone more knowledgable in these areas.

Someone more familiar with social media strategies would also be a great asset in the dissemination of the final product.

Concerns

In my proposal from last semester, I admit I struggled to define roles for the participants as many of the technical skills I’m relying on are mostly unfamiliar to me. I’m also not happy that my original proposal relied on the use of propriety software: ArcGIS StoryMap, but in my limited experience it is the program I’m most excited about as it beautifully integrates text with the map. I do not wish to pay for it, nor do I have funding for it, and I would greatly prefer being able to use an open-access platform instead. Currently this proposal isn’t very clear on what type of demographic data will be included–would it be based on Census data (how have the categories changed and is even possible to compare 1820 and 2020 data if the categories aren’t the same?). I’m also concerned that the inclusion of 2020 financial data may be tricky to include. A lot of information is based on zip codes, which are not the same as Census tracks, and there can exist much unequal distribution of wealth within very small areas (and definitely within zip codes).

Your feedback on these areas would be greatly appreciated–if we work on this project for class or I eventually pursue it in a not-so-distant future.

[This entry was originally posted to DHUM 70002 Digital Humanities: Methods and Practices (Spring 2021) in Project Proposal and tagged mapping cemeteries, project proposal on February 10, 2021.]