I finally found time this past weekend to visit my cemetery location in person. Even before the pandemic I never spent that much time downtown, but I have visited City Hall Park numerous times since moving here (13 years ago). What struck me most was how little I had paid attention before. Everything I thought I had “discovered” about the area was all laid out in a massive ground plaque near the south entrance. The public executions, the jails, that City Hall and Tweed Courthouse occupy the places where the First and Second Almshouses stood, respectively.

The plaque is a large circle of dark stone, with different segments representing different historical eras, from Dutch settlement to 1999—the date of a major renovation to the park. The plaque strikes me as something that was a much better idea on paper than it is in reality. The surface is very slick and must be very hazardous to walk over in inclement weather (the city has been sued over it: see here). In addition, it is just not very easy to read. The letters are filled with dirt, pigeon droppings, and other debris; the large segment size and the curved lines make the text and accompanying maps that much harder to read. I spent the better part of 20 minutes trying to get through it all, and I was already familiar with much of the history being relayed. It is both too much text and not enough, in my opinion. The period covered is too long for a plaque to provide any depth to the historical eras. And the particularly troubling aspects of the space have been carefully assigned to the Dutch (public executions) and British (starvation and execution of American prisoners of war). The inheritance is acknowledged, but only at a surface level (quite literally).

I spent much of my visit then walking around the entirety of the park and examining City Hall for just about every angle. I experienced many complicated feelings. It is a beautiful building, made all the more picturesque by the magnolias in full bloom. But the police were ever-present, and there are barricades all around City Hall, keeping everyone from getting very close—the seat of government barricaded from the very people it represents. (It seems like these have been left up since last summer during the George Floyd protests and subsequent short-lived Occupy City Hall movement demanding the city defund the police; see here.)

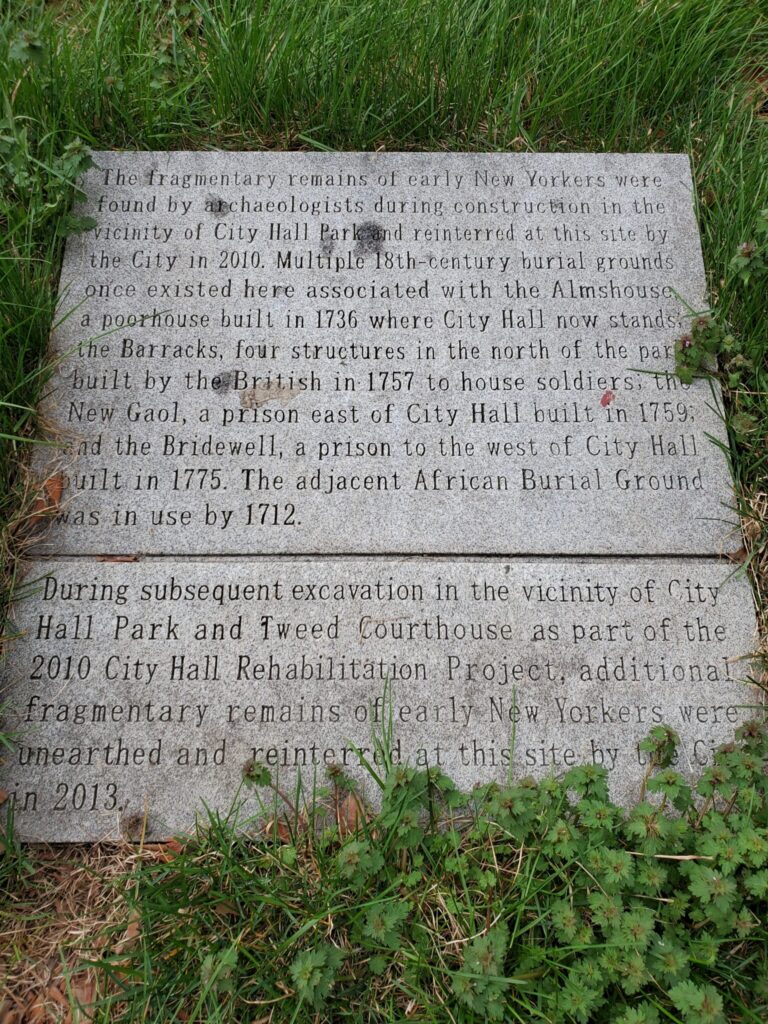

Despite knowing which corner of the park held the cemetery marker I was here to visit, it took me forever to find it. It is technically part of the park, but it is outside the nicely manicured and ornately fenced part of the park, in a more shabby small grassy area on Centre Street near Chambers Street. This marker is also light on details. These “fragmentary remains” were disturbed and reinterred here as the result of a 2010 renovation of the area, which has me wondering how many bodies were disturbed and disregarded in earlier renovations and construction projects in the space. Executed bodies, incarcerated bodies, starved bodies, poor bodies—bodies treated as a burden to the State in both life and death.

[This entry was originally posted to DHUM 70002 Digital Humanities: Methods and Practices (Spring 2021) in Personal Blogs and tagged mapping cemeteries on April 13, 2021 by Brianna Caszatt.]